Wash me thoroughly from my iniquity, and cleanse me from my sin.

For I know my transgressions, and my sin is ever before me.

(Psalm 51:2-3 NRSV)All day long my disgrace is before me,

and shame has covered my face

at the words of the taunters and revilers,

at the sight of the enemy and the avenger.

(Psalm 44:15-16 NRSV)For the needy shall not always be forgotten, nor the hope of the poor perish forever.

Rise up, O LORD! Do not let mortals prevail; let the nations be judged before you.

Put them in fear, O LORD; let the nations know that they are only human.

(Psalm 9:18-20 NRSV)Jesus went throughout Galilee,

teaching in their synagogues

and proclaiming the good news of the kingdom

and curing every disease and every sickness among the people.

(Matthew 4:23 NRSV)

Each Sunday, the Presbyterian worship service includes a prayer of confession followed by an assurance of God’s continuing grace of forgiveness, healing, help, and guidance – in short, renewal of the damaged relationship. Confession in this sense admits need, but mostly I find it narrows to admitting fault. The focus falls upon guilt summarized in the familiar phrase about those things we have done (that we ought not to have done) and those things we have left undone (that we ought to have done). Here we have the two-fold source of guilt: sins of commission (done) and sins of omission (left undone). Grace then narrows to pardon and cleansing – not counting our sins against us but washing our guilt away – and may even be degraded into the notion of another chance to get it right even though we are assured we shall fail and need pardon again. Such a misunderstanding of grace tends to have the wrong effect: instead of making us gracious toward others, it may make us continuously guilt-ridden and pressured to do life perfectly (or just better than someone else).

I am not suggesting that guilt is no great human problem. I know better, but I know also that guilt is far from being the only human problem, and currently it does not seem to be weighing so heavily on many people’s minds, especially not the minds of younger adults, as other problems in the human condition.

If I can’t breathe, I don’t cry out for water. Years ago, I heard a minister explain his decision to leave pastoral ministry for a different form by joking about what a poor preacher he had been. He said that one Sunday after the service, a church member told him, “Pastor, your sermons come like cold water to a drowning man.” Did anyone actually say that to him? I doubt it, but I think the image fits the church’s constant harping upon guilt without listening to people. Certainly there is a need for refreshment that cold water would meet nicely, but it is not the need of a person drowning. Human life is complex, human problems many and diverse, and human needs therefore varied. So narrowly has Christianity focused upon guilt that preachers and evangelists strive mightily to convince people they are guilty, must feel guilty, and will be lost if they do not acknowledge guilt as their one great problem. The Bible, however, is not so narrowly focused on guilt.

The Bible says much about shame, perhaps more than about guilt. In the Hebrew scriptures, shame is a major theme with many variations and levels of depth. Guilt is about things I have done and things I have left undone – my actions and inactions. Shame is about my very person, who I am, how I see myself, and how others regard me. In the Christian New Testament, the crucifixion narratives focus upon the shaming of Jesus more than upon his physical pain, terrible though it was. Crucifixion was designed as a public shaming reducing its victim to disgrace from which people would turn away in disgust.

This post began with four brief quotations from the Bible, only the first focused upon guilt. The second concerns shame, and the third poverty and injustice. The fourth summarizes Jesus’ ministry as teaching, proclaiming the good news of God’s kingdom, and healing the sick. In just these four short passages, a wide variety of human problems are brought before God to be set right.

In his book, Thinking the Faith, and elsewhere in his writings, the Canadian theologian Douglas John Hall has urged us to listen to the young and hear that they seem less concerned with the two-fold burden of guilt (done and left undone) than with the deeper question of whether anything is truly worth doing at all. They are seeking, not pardon, but meaning in life and hope for living it. Now I see that in his book I’m reading, Ill Fares the Land, the historian Tony Judt recognizes also the uncertainty of the young, their confusion about what direction to take and why. Do our choices really matter? Is any direction worth the effort of taking? More pointedly perhaps, can we do anything to fix the mess we, the human race, have made of this world, or would earth be better off if we made our exit? Should we try to change things or just survive with as little discomfort as possible? If we do want to change things for the better, how? These are questions seeking meaning and purpose on the edge of hopelessness. What is needed is not mere optimism but substantial hope that can be pursued.

What I am asking in this blog post is that we, Christians and our churches, widen our view of human life, need, and salvation. Guilt is not our only problem. Neither is getting into heaven our only goal or even the primary goal of faith in Jesus Christ. Salvation is relational not transactional, which means it’s not a deal Christ has cut to get us into heaven after we die. Salvation is the restoration of relationship with God, other people, the human community, the created order, and ourselves – here and now.

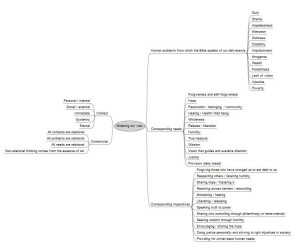

To help myself visualize complex matters, I sometimes use a computer program called FreeMind. I’m attaching an image of the FreeMind diagram I’ve done this morning called “Widening Our View.” I know it is not complete, but it’s purpose is start visualization of a wider view of the biblical message of hope for us and our world. I find it helpful, and so I share it. Maybe our message, the hope we share, can become less like cold water to a drowning person. Click the image to read it.